Infinitely Scalable Applications

We’re going to talk about a type of scale that’s often an afterthought. Scale is often associated with ensuring that our application remains performant with increasing users. But there’s another side to scale that we overlook too often.

We’re often so focused on scaling our infrastructure that we don’t take equal time to structure our codebase for an increasing number of team members and features. As projects grow, growing mental overhead leads to slower engineering velocity and spaghetti code.

Over the past few years, modern monorepo tools have gradually made their way from the platform teams of large tech companies to the open-source community, unlocking new workflows and architecture patterns.

In this post, we’re going to walk through one way to leverage these tools to take a single application and scale it to an entire ecosystem of applications and packages. We’re going to optimize for three tenets:

- Fast iteration velocity with clear separation of concerns at every point of scale

- High business agility through efficient code re-use

- Scalable tasks (

build/test/lint) that are decoupled from application size

Key Concepts

I want to take a moment to explain some foundational tools that we’ll use to structure our project.

Composition

If you’ve used React, you’re probably familiar with composition principles. To make a component highly reusable, its props should be structured around what it does instead of where it’s used. We then compose these components together and pass them context-specific logic.

This pattern is called inversion of control, and Kent C. Dodds has a great blog post about it if you want to learn more. Instead of composing components together to build a page, we’re going to compose packages together to build an application.

Applications as a point of composition

The term "application" usually refers to the deployable artifact that our users see. I’m going to use the word “application” to refer to the directory containing our application’s package.json. This is where we list all the dependencies, either local to the monorepo or external in a registry, that we’ll need to build or compose our application.

Packages as a boundary

Packages are mainly used for sharing code, either by open-sourcing it on NPM or keeping it in a private registry for internal teams.

When we package code from an application, we take on the task of managing dependencies and using a different toolchain. In exchange, we get a stronger separation between portions of our codebase and the ability to reuse that segmented logic in an entirely different context.

We’re going to focus on using packages as a way to define strong boundaries in an ever-growing codebase.

Scaling a single application

The Problem of Disorganization

If you’re in the early stages, you’ll start with a handful of directories to organize logic. You might have a folder named /components that contains all your React components. You might also have a folder that becomes a bottomless pit of random functions named /utilities or /lib.

When working on a codebase with more than 20 files in each directory, it can be challenging to locate existing logic that can be reused or determine the appropriate location for new logic when boundaries become unclear.

Feature Folders

At this stage, our focus is on optimizing for clarity in code usage. To achieve this, let's start by organizing our codebase with an additional level of hierarchy. This will categorize our code based on the specific use case intended for each file.

For example, if your directory structure contains a lot of authentication and checkout logic

├─ ui/

│ ├─ checkout-button.ts

│ └─ user-avatar.ts

├─ utilities/

│ └─ format-price.ts

└─ data/

├─ get-product-information.ts

└─ get-is-authenticated.tsyou’ll be able to organize these into dedicated /feature-checkout and /feature-auth folders.

├─ feature-checkout/

│ ├─ ui/

│ │ └─ checkout-button.ts

│ ├─ utilities/

│ │ └─ format-price.ts

│ └─ data/

│ └─ get-product-information.ts

└─ feature-auth/

├─ ui/

│ └─ user-avatar.ts

└─ data/

└─ get-is-authenticated.tsReducing mental overhead

You can create use-case folders incrementally and move files in as features mature. I've found the feature- prefix helpful because it distinguishes files that have a clear purpose from files that may not have a narrow scope yet and still reside in those root-level folders.

Need to add a new UI component for a pricing page? There’s a folder for that.

Need a utility to fetch user information for a login flow? There’s a folder for that, too.

By optimizing for the tasks your developers are trying to accomplish, this structure reduces mental overhead and prevents files from taking on too many responsibilities, thus avoiding spaghetti code.

Decomposing a monolith

Organizing your code by feature will go a long way, but at some point, you'll run into the same issue you had with files, but this time with feature folders.

Frameworks often offer the best developer experience when all your code is placed within your application directory. However, you’ll start to notice a change as your codebase becomes larger.

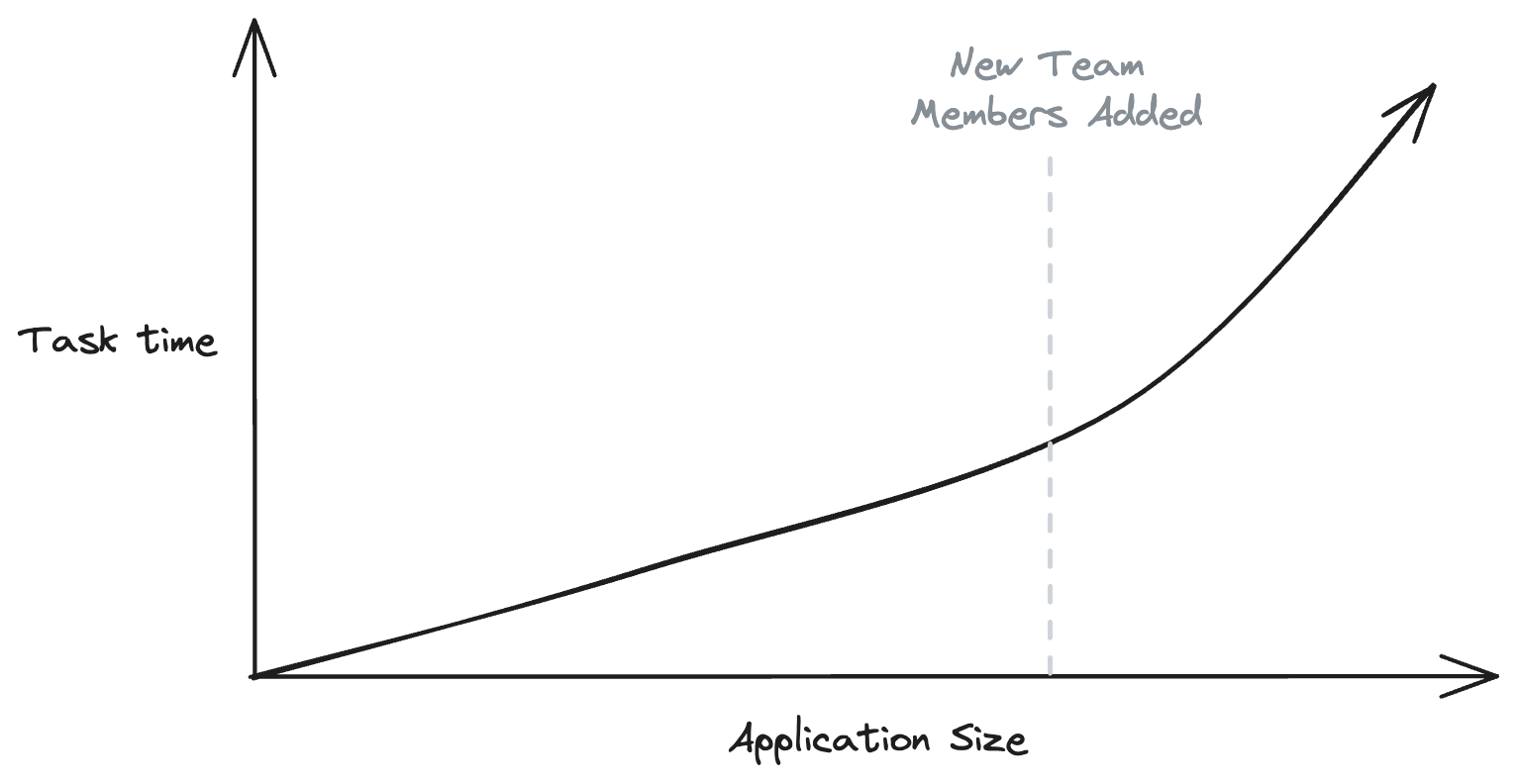

A graph showing increasing task time as applications get larger

The time it takes to run tasks like build, test, and lint will increase linearly with the amount of code in your application. Adding new developers to the project will increase the rate at which new code is added, exponentially accelerating this issue.

We shouldn’t have to choose between the growth of our business and reasonable task times. The good news is that you don't need to!

We're going to use packages to create a stronger boundary between our features and our application. This boundary will not only result in a stronger separation of concerns as we add more feature-specific code but also enable us to break up task time.

From Feature Folder to Feature Packages

We’ll begin by taking the first step in decomposing our application. First, we’ll create /app and /packages folders at the root of our project.

my-app (root)/

├─ apps/

├─ packages/

└─ src/

├─ feature-checkout/

│ ├─ ui/

│ │ └─ checkout-button.ts

│ ├─ utilities/

│ │ └─ format-price.ts

│ └─ data/

│ └─ get-product-information.ts

└─ feature-auth/

├─ ui/

│ └─ user-avatar.ts

└─ data/

└─ get-is-authenticated.tsNext move everything in the root directory into a new application folder in the /apps directory and rename the root directory.

my-monorepo (root)/

├─ apps/

│ └─ my-app/

│ └─ src/

│ ├─ feature-checkout/

│ │ ├─ ui/

│ │ │ └─ checkout-button.ts

│ │ ├─ utilities/

│ │ │ └─ format-price.ts

│ │ └─ data/

│ │ └─ get-product-information.ts

│ └─ feature-auth/

│ ├─ ui/

│ │ └─ user-avatar.ts

│ └─ data/

│ └─ get-is-authenticated.ts

└─ packages/To enable monorepo development, we need to configure our package manager.

We'll use pnpm in this case, but Yarn or NPM workspaces will also work. We need to tell pnpm that all packages are within the /apps and /packages directories.

pnpm-workspace.yaml

packages:

- "packages/*"

- "apps/*"We’re going to move our checkout feature into it's own package. We'll take everything that was in the /feature-checkout folder and move it into our new package’s /src directory.

/my-monorepo (root)/

├── /packages/

│ └── /feature-checkout/

│ ├── /ui/

│ │ └── checkout-button.ts

│ ├── /utilities/

│ │ └── format-price.ts

│ ├── /data/

│ │ └── get-product-information.ts

│ └── package.json

└── /apps/

└── /my-app/

├── package.json

└── /src/

└── /feature-auth/

├── /ui/

│ └── user-avatar.ts

└── /data/

└── get-is-authenticated.tsTo create a new feature package, navigate to the /packages directory, create a new package.json file, and give it the same name as the previously named feature folder.

packages/feature-checkout/package.json

{

"name": "@package/feature-checkout",

"version": "0.0.1",

"private": true,

"main": "src/index.ts",

"types": "src/index.ts"

}You may notice that our entry point references an uncompiled TypeScript file. We delegate the compilation of this package's code to the application, allowing you to create packages that provide the same developer experience as if the files were built directly into our application. This is known as the internal package pattern, and there are some great code samples in the TurboRepo documentation.

Unlike files directly created in our application, we can use package entry points to control which files are exposed to the rest of our ecosystem. This provides another way to create a stronger separation of concerns.

We're also making this package private because we don't want to publish uncompiled TypeScript. However, if you're using vanilla JavaScript and your code doesn't require a build step, you're free to publish! This is a great example of where the Types as Comments proposal would have a significant impact, so it's good to keep an eye on its progress.

Lastly, we’re going to add our feature package as a dependency of the application.

apps/my-app/package.json

{

"name": "my-app",

"dependencies": {

"@package/feature-checkout": "workspace:*"

}

}The workspace:* syntax tells pnpm to use the most recent version of your package within the monorepo. You can still use semver to version your packages and tag releases using a tool like Changesets.

It is important to treat feature packages as an extension of your application. I recommend keeping dependency versions and NPM script names in sync.

If you try to install multiple versions of the same dependency in a monorepo, you could run into some bugs you might not expect. You might accidentally install two versions of a package that use React context and encounter referential equality bugs when the consumer and provider are out of sync.

Keeping NPM script names consistent will make it easy to add a task runner such as NX, TurboRepo, or wireit.

Distributing Tasks Across the Dependency Graph

With this architecture, we get the same great developer experience as working in a single application, with one big difference. If we add scripts like lint or test to this package, we can run and cache the results of those tasks separately from those that run on our application. Tasks will only run on packages that have changed or whose upstream dependencies have changed.

As we refactor more feature folders into feature packages, our application becomes thinner and thinner.

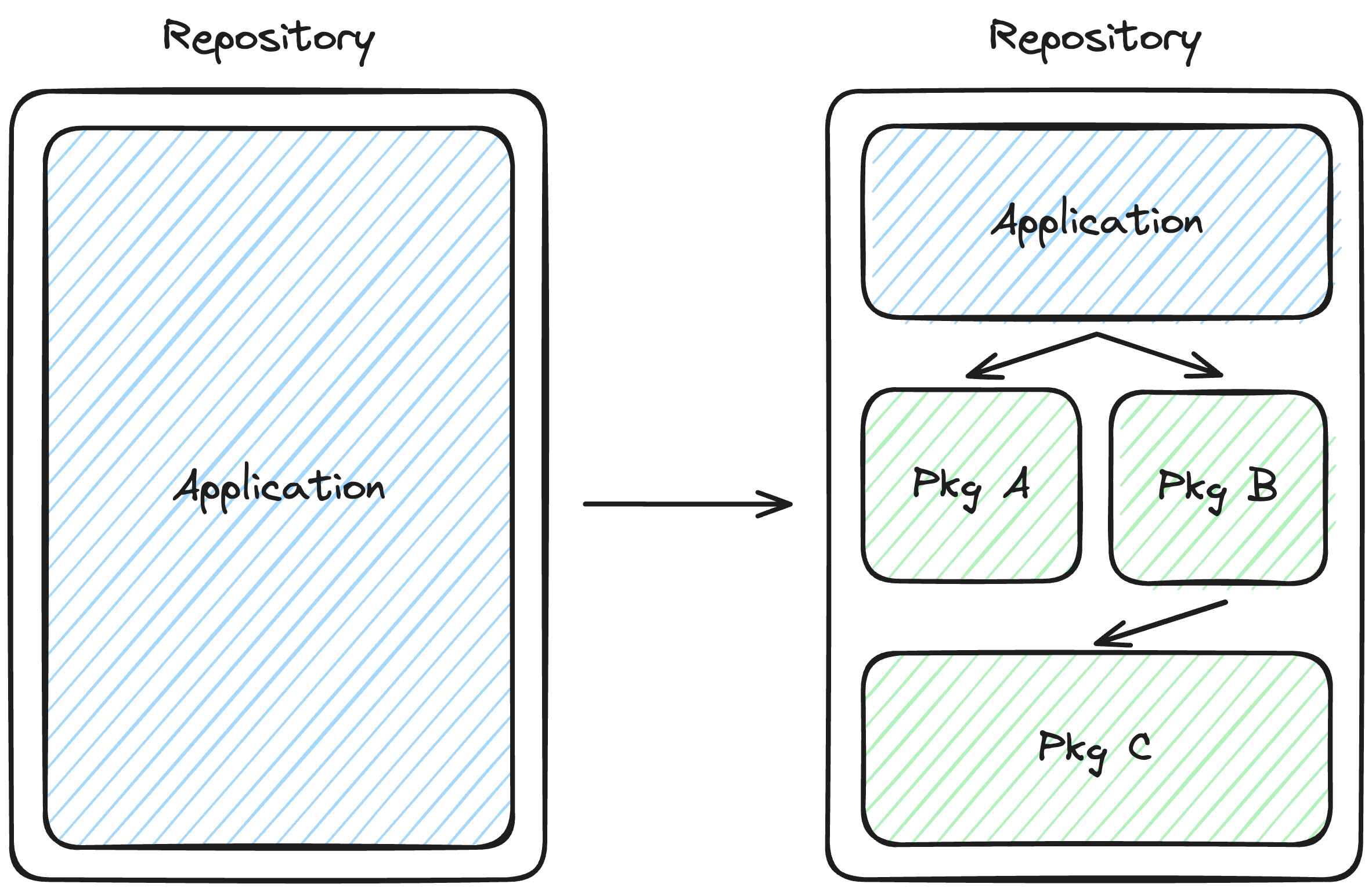

The transition from a monolith to a thin application built on a foundation of packages

The pattern of thin applications built on an ecosystem of packages treats your application as the point of composition for feature packages. It narrows the responsibility of your application to bundling, data loading, rendering, and routing.

If you want to reduce the execution time of your build task, you can add a build script to your feature package and distribute the execution in the same manner as any other task.

Optimizing for Business Agility and Technical Flexibility

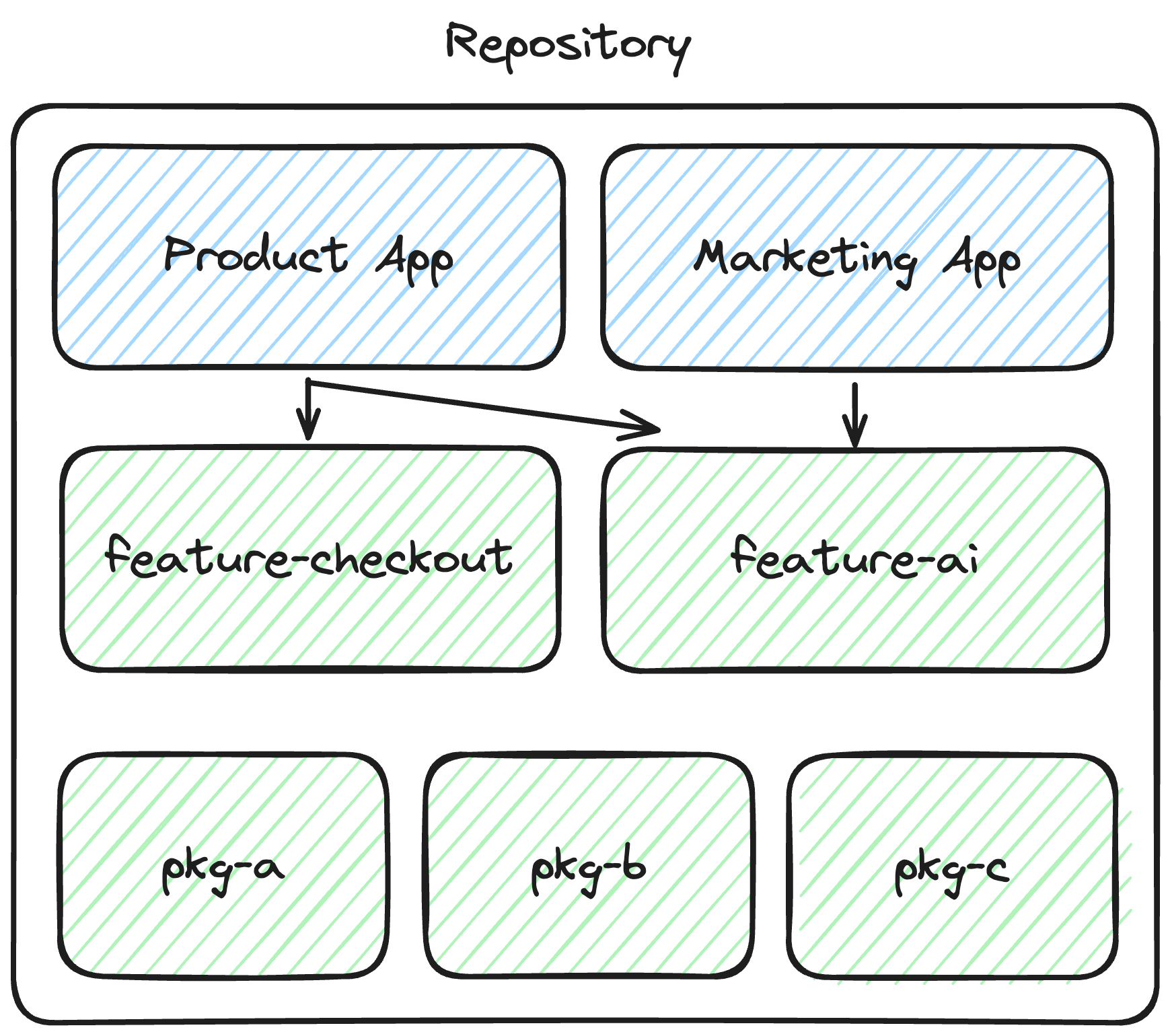

The value your engineering team creates isn’t in an application; it’s in the features your team builds to solve the problems of your customers or your business. Optimizing for re-use of these features will accelerate engineering velocity and give your business the agility to pivot and quickly re-compose existing features. Let’s explore a real-world scenario where this pattern shines.

Easily reuse features across applications

Imagine that your new AI product is taking off, and you want to create a marketing site where visitors can experience a demo of your new chatbot.

To make your AI feature shareable, you would typically need to invest time and resources into separating it from your application. Initially, you may have created a separate package for your AI feature solely for task performance. However, with package composition, you can easily reuse it in a completely different business context without any upfront investment.

We may not know what the future holds, but we can optimize for any future.

Scaling an ecosystem

Hopefully, in the future, your team will grow. Maybe you started with a few developers but now have 10+ teams working on your product. When you have this many developers contributing to a single monorepo, you might start experiencing some workflow issues.

The number of PRs to your monorepo might become overwhelming. You may introduce a merge queue to alleviate some friction, but depending on team size, that queue might take an hour or longer to merge into main.

You might find that teams have perfectly valid reasons to use different versions of dependencies. Maybe you have multiple products in the same monorepo with entirely different development and release workflows.

The next step to address these issues is to find the boundary between business domains within your monorepo and break it down into multiple monorepos.

Splitting your monorepo

When breaking down a monorepo, the first instinct is to divide it by team. While teams might sometimes align with a business domain, it’s important to structure your repositories in a way that doesn’t require a major refactor when reorganizations happen.

The mantra that has always helped me is “what changes together, stays together”. You don't want to have a workflow where two tightly coupled packages are developed across different repositories. This would require going through the build -> version -> publish -> validate workflow for every pull request and cause a lot of frustration.

To share packages across monorepos, you’ll need to build and publish your feature packages. This will enable the same level of business agility that we had before but across different business domain monorepos.

Common questions

A few questions consistently come up while implementing this architectural pattern.

How Big Should Packages Be?

Packages can be one file or one hundred files. Some packages need more logic, even if the scope of that package is narrow. You can imagine that a database ORM package needs more files than a resizable text area.

As long as you maintain a narrow scope for your package it doesn’t matter how many files you package contains. A better question to ask is “How many things is this package responsible for?”

Can I publish my packages to a registry early on?

Definitely! If you want to make it easier to idenpendently consume a portion of your open source project you can just add a build step and publish it.

If you're working at a larger company, it's common for your peers to look at what you're working on and want to leverage some of the great work you've done.

Because that team probably has a specific idea of what they want to reuse that will translate well to a narrowly scoped package.

More monorepo tools

Monorepo tooling is still not completely frustration-free, but many projects are making it easier to get started. Here is a non-exhaustive list of some useful tools that I have found helpful in the past for managing monorepos with many packages.

pnpm: Fast, disk space efficient package manager

NX: Next generation build system with first class monorepo support and powerful integrations.

Turborepo: Turborepo is a high-performance build system for JavaScript and TypeScript codebases.

Changesets: A way to manage your versioning and changelogs with a focus on monorepos

Manypkg: Manypkg is a linter for package.json files in Yarn, Bolt or pnpm monorepos.

syncpack: Consistent dependency versions in large JavaScript Monorepos.

A vision of the future

Think of our starter application as a big blob of clay. It doesn't have any real shape which makes it difficult to figure out where the boundaries of logic are.

When we refactored a bit of logic into a feature package, we gave definition to a subset of that code blob. We can add documentation to that package to provide even more context about how it should be used and create a CODEOWNERS file to assign ownership to the package. We transformed a piece of our clay into a building block with a distinct shape and a defined method of connecting to other building blocks.

Now, imagine that the majority of your codebase is made up of clearly defined building blocks. Layer on the dependency graph, and you have an indexable data structure that would be extremely difficult to re-create in a single application.

What if we could layer AI on top of that, tell it what we want to build, and get back an instruction book of all the building blocks available to us, who owns them, and which ones need to be created to reach our goal?

Imagine a world where the needs of your engineers are proactively communicated to the teams best suited to address them. A world where no work is duplicated and engineering velocity is exponentially accelerated by leveraging the work of those who came before.

This is the future I want to build, and if you want to come along for the ride, you can follow me at @alecchernicki